Overview

“This provocative new book is exactly what it sounds like: an account of how Gen. Ulysses S. Grant issued an order to expel Jews from their homes in the midst of the Civil War. Anyone seeking to rock the Passover Seder with political debate will find the perfect conversation piece in Sarna’s account of this startling American story. . . . His book is part of the prestigious series, matching prominent Jewish writers with intriguingly fine-tuned topics.”

—Janet Maslin, The New York Times “Powerful. . . . Sarna’s brilliantly nuanced exploration of the worst official anti-Semitic incident in American history offers us a clear reminder in these ideologically fraught days of why keeping up a firm wall between church and state remains a core defense for all of our freedoms. This wide-ranging and judiciously balanced book is the latest entry in the luminous Schocken/Nextbook Jewish Encounters series of books [that] thoughtfully pair a great writer and an important facet of Jewish life.” —Marc Wortman, The Daily Beast “Richly researched [and] filled with lively, little-known personalities . . . it also contains reams of juicy quotes and delicious bits of doggerel.” —Jenna Weissman Joselit, The New Republic “An interesting history about a little-discussed event during the Civil War.” —St. Louis Post-Dispatch “Sarna’s book is going to make a significant splash amidst a wave of new books reevaluating the career of one of our most famous army general/presidents. . . . Most compelling.” —John Marszalek, Moment magazine “Ulysses S. Grant’s order expelling Jews from his war zone has long helped insure his eternal disgrace. Supposedly, the drunken, bloodthirsty crook was also an anti-Semite! Jonathan Sarna’s excellent, painstaking reevaluation of what really happened helps rescue Grant’s reputation; it is long overdue. It also affirms Sarna’s unsurpassed standing as a historian of American Jewry.” —Sean Wilentz, author of The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln “An excellent study [from the] gifted and resourceful historian Jonathan D. Sarna . . . His account shines brightest around the edges of the story, offering valuable new insights into ethnic politics, press power, and the onetime ability of leaders to flip-flop with grace . . . A compelling page-turner.” —Harold Holzer, The Washington Post “Thoroughly researched and crisply written, this is a very fine work that will interest students of both American and modern Jewish history.” —Publishers Weekly “Sarna expertly navigates the repercussions of Grant’s shocking order, which galvanized the American Jewish community into action, reminding many who were refugees from European expulsions how insecure they were even in America. . . . Sarna weighs the short-lived order against important Jewish appointments in Grant’s administration, his humanitarian support for oppressed Jews around the world, and lasting friendships with Jews. A well-argued exoneration of a president and a sturdy scholarly study.” —Kirkus Reviews “In this compelling and focused study, Jonathan D. Sarna explores the causes—and assesses the little-known impact—of one of the most troubling incidents in the life of the Union's greatest commander.” —Geoffrey C. Ward, coauthor of The Civil War “An absorbing account of a lamentable act by the North’s greatest general, a dishonorable act committed by an honorable man. This fair and balanced treatment of the event places the commander and the Jews in the context of great conflict. Fortunately, redemption and rapprochement would follow.” —Frank J. Williams, president, Ulysses S. Grant AssociationOn December 17, 1862, as the Civil War entered its second winter, General Ulysses S. Grant issued a sweeping order, General Orders #11, expelling “Jews as a class” from his war zone. It remains the most notorious anti-Jewish official order in American history. The order came back to haunt Grant in 1868 when he ran for president. Never before had Jews been so widely noticed in a presidential contest, and never before had they been confronted so publicly with the question of how to balance their “American” and “Jewish” interests. During his two terms in the White House, the memory of the “obnoxious order” shaped Grant’s relationship with the American Jewish community. Surprisingly, he did more for Jews than any other president to his time. How this happened, and why, sheds new light on one of our most enigmatic presidents, on the Jews of his day, and on America itself.

Reader's Guide

In the middle of the Civil War, on December 17, 1862, General Ulysses S. Grant issued General Orders No. 11, which called for the expulsion of “Jews as a class” from the Department of the Tennessee – a vast area stretching from Mississippi to Illinois. The order was revoked almost immediately by President Lincoln, and its direct effects on the country’s small but growing Jewish community were limited. Yet the unprecedented decree had enormous unintended consequences, not just for Grant but for American Jewry. The effects, in fact, continue to reverberate today. General Orders The Jewish community in America was relatively small when the Civil War broke out; despite a recent surge in immigration in the mid-19th century, there were still only 150,000 Jews in America, less than 1 percent of the population. Still, that made the Jews the largest non-Christian minority in the country. And during the war, as Jonathan Sarna explains, anti-Semitism reared its head, and Jews as a group came under frequent attack for everything from smuggling to profiteering.

-

Smuggling was, indeed, a major problem vexing Grant in his war effort against the Confederacy. And some of those smugglers were, in fact, Jewish. But Grant’s order, motivated in large part by his desire to squash the smuggling, implicated all Jews “as a class.” Why is this phrase particularly important?

-

Sarna suggests that one of the main motivations behind General Orders No. 11 was personal for Grant: His father had gotten involved in a corrupt scheme involving a group of Jewish smugglers, and the enraged general displaced his anger at his father onto Jews, “as a class.” Do you think this had something to do with the order? If, in fact, the animus behind the decree was personal rather than broadly anti-Semitic, does that change your impression of Grant and his actions?

-

Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation just two weeks after Grant’s order. The timing of these two decrees – one freeing blacks, the other expelling Jews – did not go unnoticed; in Memphis, the Daily Bulletin printed the two documents on the same page, one above the other. Jews, Sarna writes, “feared that Jews would replace blacks as the nation’s stigmatized minority.” Do you think those fears were justified at the time?

-

The total number of Jews who were actually expelled, Sarna writes, seems to be less than a hundred, mostly in small towns in northern Mississippi. Why, then, is this such an important moment in American Jewish history? Do you think that statements comparing Grant to Haman – the villain of the Purim story in the Book of Esther – were overstated?

-

Poor communication during wartime meant that Grant’s order was not received by military commanders in a timely fashion, and many who did receive it had questions regarding its implementation, and so it was not widely enforced in the weeks after it was issued. If those commanders had enforced the order – and applied it to Jewish soldiers fighting in the Union army, and Jewish peddlers who sold goods to army camps, who were not exempted – how might that have affected public opinion about it? What if those commanders had made a public stand, as at least one general did, by explicitly refusing to enforce the order at all, rather than asking for clarifications?

-

Isaac Mayer Wise, a prominent rabbi and newspaper editor in Cincinnati, called the order an “outrage, without a precedent in American history,” and editorialized in his newspaper The Israelite that Jews “as a class…have officially been degraded.” He urged Jews to seek redress, but also cautioned, as Sarna explains, “that too strong a Jewish protest could backfire.” What was Wise afraid might happen if Jews protested the order too loudly? Were his fears well grounded?

-

A businessman named Cesar Kaskel – a Jewish immigrant in Paducah, Kentucky – was one of the few to be expelled from his home, and Kaskel set out to overturn Grant’s order personally. He spread word about the decree to newspapers and Jewish communal leaders, and traveled to Washington to appeal to President Lincoln directly. Securing a personal meeting with the president, Kaskel asked for his protection for the Jews, which Lincoln offered at once, revoking the order on January 6, 1863. What do you think might have happened if Lincoln had not granted this ordinary citizen a personal audience? How important was Kaskel in overturning the decree, compared to other politicians, newspaper editorialists, and communal leaders?

-

For many Jews, especially in the north – where Grant was a national hero after the war – the 1868 vote posed a difficult quandary: Should they vote for a man who was good for the country, even if they thought he was bad for the Jews? Do you think this question is still relevant in political campaigns today? In what way does this kind of question emerge in modern elections? What are the key “Jewish” issues for a presidential contender in the 21st century?

-

Grant disavowed General Orders No. 11 in a private note in September 1868, in response to a letter from a leader of B’nai Brith. “I do not sustain that order,” he wrote. “I have no prejudice against any sect or race, but want each individual to be judged by his own merit.” While this letter was not published until after the election, it did have an effect on the election behind the scenes, as influential Jews circulated the letter privately and then made their feelings about Grant known in talks, and letters to newspapers; “it did much to rehabilitate his image in Jewish eyes,” Sarna explains. Why do you think Grant declined to make the letter public until after the election? Do you think it could have backfired if he’d distanced himself from the order too publicly, during the campaign?

-

In the 1868 campaign, Jews “campaigned as Jews” for the first time, Sarna writes. In other words, while Jews had been politically involved before, in 1868 “more Jews than ever before justified their political loyalties on the basis of their religion.” Not only did the Jewish community feel more specifically bound together, but the notion of a Jewish voting bloc became known to other Americans as well during this time. What has the legacy of this “public display of power” been? Do you think the cohesion of the “Jewish vote” has increased over the past century and a half? Do you think conventional wisdom about the power of the “Jewish vote” is exaggerated today?

-

If a politician today had a record that included explicitly anti-Semitic statements and actions, do you think he could make a successful run for the White House? If such a candidate made a private apology during the campaign, do you think the Jewish community today would be so quick to forgive him?

-

While the appointment of Jews to a record number of government posts was seen as a “golden age” for American Jewry, according to Sarna, many of the posts themselves sound relatively minor: Recorder of Deeds for the District of Columbia, a consul in British Columbia, deputy postmaster in Jefferson, Texas. Why was it important that even such minor appointments were made? What message did it send to American Jews – and gentiles?

-

A few of Grant’s Jewish appointments were more prominent: governor of Washington Territory, superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Arizona territory, consul-general to Romania. “During his administration, Jews won growing acceptance within American life,” Sarna writes. Were high profile appointments a reflection of that growing acceptance, or did the appointments themselves drive the acceptance?

-

The newly empowered American Jewish community demanded political action in response to anti-Semitism in Russia and Romania during Grant’s administration – and the president responded. “By joining with Grant in appealing to high-minded human rights claims,” Sarna writes, “Jews looked to be shaping an America that explicitly promoted ‘one universal law of humanity.’” How do we continue to feel the effects of this change in American policy today? Is the American Jewish community still at the forefront of political action to promote human rights internationally?

-

When Grant ran for re-election in 1872, General Orders No. 11 resurfaced as a campaign issue, but this time was quickly defused. Rabbi Wise, not originally a supporter of Grant, admitted that “we have long ago forgiven him that blunder” by 1872; even southern Jews, who had voted against Grant the first time, came around to the Republican side. Do you think the same forgiveness still applies to politicians today, or are we less willing to believe that people can genuinely change their views?

-

Toward the end of his presidency in 1876, when re-election was no longer an issue, Grant became the first president to attend a synagogue dedication, at Adas Israel in Washington, D.C. He even made a personal donation to the congregation. Why was this visit symbolically important? Would it have been as important if he’d visited a synagogue four years earlier, while he was on the campaign trail, hoping to score Jewish votes?

-

Soon after leaving office, Grant took a trip around the world, and became the first American president to visit Jerusalem. Today, trips to Israel are routine for American politicians seeking high office, but at the time, the Jewish community in Palestine was still relatively small. How significant do you think Grant’s visit to Jerusalem seemed to American Jews at the time?

-

Sarna writes that General Orders No. 11 “proved difficult for [Grant] to live down; he spent the rest of his life making amends for it.” Do you think much of Grant’s activism – on behalf of American and international Jewry, and human rights – came from his motivation to “make amends” rather than a strong conviction? Does it matter to you what his motivation might have been?

-

As time progressed after Grant’s death, and his record was reconsidered in retrospect, historians have remembered General Orders No. 11, but not always the years of work he spent working with the Jewish community in its aftermath. Do you think General Orders No. 11 should remain an indelible stain of anti-Semitism on his record – or, in the wake of so many positive moves that followed, should it become a more minor footnote in the history of a man who became a friend to the Jewish community? Can the decree be forgiven?

- Grant’s decree motivated the American Jewish community to organize around political issues for the first time. And Grant’s presidency gave American Jews unprecedented power within American politics for the first time. How do we feel the reverberations of these events today?

News and Reviews

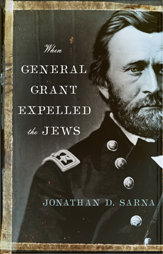

When Grant Expelled the Jews “A well-argued exoneration of a president and a sturdy scholarly study”

Sarna (History/Brandeis Univ.; A Time to Every Purpose: Letters to a Young Jew, 2008, etc.) nimbly reappraises Grant’s presidency as ushering a “golden age” for American Jews, despite the short-lived expulsion order he couldn’t live down. General Orders No. 11, published in 1862 by Gen. Grant as head of the Union Army’s Department of the Tennessee, decreed that “Jews as a class” were to be expelled from the department because of “violating every regulation of trade”—i.e., on account of smuggling. While the order was issued during the pressing exigencies of wartime, then swiftly revoked by President Lincoln when visited by prominent Kentucky merchant Cesar Kaskel and Ohio Congressman John Addison Gurley some weeks later, Grant was vilified by the Jewish community—nearly 150,000 citizens—and hard-pressed to exonerate himself as presidential candidate, then president. Sarna expertly navigates the repercussions of this shocking order, which galvanized the American Jewish community to action, reminding many who were refugees from European expulsions how insecure they were even in America. It also deeply divided the Jewish community when faced with the 1868 Grant-Seymour presidential election. The order aroused a passionate debate both in the Senate, where some Democratic members moved to censure the (Republican) general, unsuccessfully, and in the press, which spoke out against the stereotyping and scapegoating of the Jews as “swindlers.” (Sarna evenhandedly considers the extent to which Jews were involved in smuggling.) Moreover, with the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation, Jews expressed their consternation that the rise in status for blacks came at the cost of their own abasement. Jewish leaders such as Simon Wolf and Isaac Mayer Wise wrestled with the ethics of backing the modern-day Haman, as Grant was called, or support the racist, anti-black Democrats. Sarna weighs the short-lived order against important Jewish appointments in Grant’s administration, his humanitarian support for oppressed Jews around the world and lasting friendships with Jews. A well-argued exoneration of a president and a sturdy scholarly study. Continue reading

When Grant Expelled the Jews “thoroughly researched and crisply written”

"Thoroughly researched and crisply written, this is a very fine work that will interest students of both American and modern Jewish history." Continue reading

When General Grant Expelled the Jews praised in Library Journal

“This book, the most detailed study of the topic to date, takes readers from the issuing of the order to Grant’s demise. Sarna sheds light on a little-known aspect of the Civil War and the experience and treatment of Jews during the mid-to late 19th century. A valuable addition to all collections for Civil War and presidential history buffs and specialists, as well as for students of American Jewish history.” Continue reading

Leading historian of the Jewish experience Jonathan Sarna “agrees with critics (and Grant himself) that ordering the evacuation was a gigantic blunder” in When General Grant Expelled the Jews

"Brandeis professor Jonathan Sarna examines the order and the long-standing criticism of Grant; the result is the most compelling contextualization available on the issue." A leading historian of the Jewish experience in America, he Continue reading

Sarna is a “gifted and resourceful historian,” and When General Grant Expelled the Jews is a “compelling page-turner.”

“Sarna’s account shines brightest around the edges of the story, offering valuable new insights into ethnic politics, press power and the onetime ability of leaders to flip-flop with grace...Sarna’s excellent study offers no excuses...and comes closer than ever to an explanation.” Continue reading

“Sarna did a great job with this book”

“The Brandeis professor did a marvelous job with looking into a glimpse of Grant's life and its effect on Jewish-Americans.” Continue reading

When General Grant Expelled the Jews “highly recommended”

“This book is highly recommended to those interested in the Civil War and American Jewish history.” Continue reading

When General Grant Expelled the Jews: “Yes, this a non-fiction book – who would have thought?”

“Well-written and well researched.” Continue reading

When General Grant Expelled The Jews perfect to “rock the Passover Seder with political debate”

"Anyone seeking to rock the Passover Seder with political debate will find the perfect conversation piece in Mr. Sarna’s account of this startling American story. Last graph: Mr. Sarna’s book is part of a prestigious series matching prominent Jewish writers with intriguingly fine-tuned topics." Continue reading

Jonathan Sarna describes the plight of Paducah’s first Jewish Activist in The Times Opinionator

“I, a peaceable, law abiding citizen, pursuing my legitimate business at Paducah, Kentucky, where I have been a resident for nearly four years, have been driven from my home, my business, and all that is dear to me, at the short notice of twenty-four hours; not for any crime committed, but simply because I was born of Jewish parents,” said a young merchant named Cesar Kaskel to reporters in late December 1862. The accompanying headline disclosed why Kaskel was so abruptly ordered out. It read: “Expulsion of Jews from General Grant’s Department.” Continue reading

“Father Abraham and the Jews” recounts the tale behind When General Grant Expelled the Jews

"In his recent book, “When General Grant Expelled the Jews,” Brandeis University Professor Jonathan D. Sarna recounts an important but little known event in 1863 in Lincoln’s quest for full civil, religious and human rights for all Americans — this time, for American Jews." Continue reading

About the Author

Jonathan Sarna

Jonathan D. Sarna is the Joseph H. & Belle R. Braun Professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University. He also chairs the Academic Advisory and Editorial Board of the Jacob Rader Marcus Center of the American Jewish Archives in … Continue reading