Overview

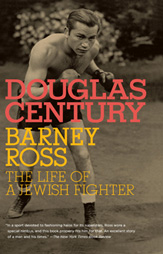

A powerful storyteller brings to life one of the most colorful boxers of the 20th century.

Barney Ross’s story is the stuff of legend. At 13, Dov-Ber Rasofsky witnessed his father’s murder, his mother’s nervous breakdown, and the dispatching of his three younger siblings to an orphanage. Vowing to reunite the family, Ross became a petty thief, a messenger boy for Al Capone, and, eventually, an amateur boxer. Turning professional at 19, he would capture three titles in his 10-year career. In 1941, at the age of 32, Ross requested combat duty in the U.S. Marine Corps and earned a Silver Star for his heroic actions at Guadalcanal. While recovering from war wounds and malaria he became addicted to morphine, a habit he would finally kick. Ross also ran guns to Palestine and offered to lead a brigade of Jewish American war veterans. This galvanizing account of Ross’ emblematic life is a revelation of both an extraordinary athlete and a remarkable man.Book Excerpt

On December 13, 1923, ten days short of his fourteenth birthday, Barney was dressing in his ROTC uniform for a morning drill at the Joseph Medill School when a gunshot echoed on Jefferson Street. Rushing downstairs, he heard a cry of “Gonovim!” A small crowd had formed around the grocery, and Beryl pushed his way inside. His father lay on the floor, blood soaking through his white apron, shot in the chest. Beryl tore at his father’s clothes, ripped off the apron and his shirt and tzitzis. “It’s alright, Beryl,” Itchik said. Ambulance attendants rushed inside the grocery; Beryl heard the sound of his mother shrieking as his father was carried away. The shooting made the afternoon edition of the Chicago Daily News:

GROCER, 60, SHOT IN FIGHT WITH ROBBERS

Two negroes entered the grocery of Isaac Rosofsky, 60 years old, 1303 [inaccurate address but verbatim from news story] Jefferson Street, this morning and purchased 5 cents worth of apples. The grocer handed the apples to the men and they drew pistols and ordered Rosofsky to “stick them up.” The grocer refused to obey and made for the men. He fell in his tracks with a bullet in his chest. Rosofsky’s family . . . heard the shot and came out just in time to see the robbers flee south in Jefferson street.

In the county hospital, Itchik hovered in and out of consciousness for thirty-two hours, then, as Barney later remembered, he “awaked once to put a hand on a rheumatic shoulder which had bothered him for years and whisper, ‘It doesn’t hurt anymore.’” He rubbed his beard and muttered “Sh’ma Yisroel [Hear, O Israel]” before dying. The funeral was held in the cramped Rasofsky apartment, women wailing, mirrors draped with blankets. Barney and his older brothers stood to say Kaddish and the littlest ones—Sammy, Georgie and Ida—strained to see their father’s casket as it was carried through the crowd on Jefferson Street into the hearse for internment in Jewish Waldheim Cemetery.

In the days following the murder, Sarah Rasofsky fell to pieces. She was hospitalized with a nervous breakdown, said she could no longer bear to live in the apartment across the street from the murder scene. In Barney’s memory of the funeral scene, his mother had been so grief-stricken that she tried to throw herself into her husband’s open grave. Double-chinned, she is often seen smiling broadly in the photographs from Barney’s glory years as a world’s champion; yet the pain and rage was forever smoldering. Years later, visiting her husband’s grave site—still so observant that she would not go with any of her kohain sons, only entering the gates of Jewish Waldheim in the company of nieces and female cousins—she would scare the little girls by convulsing as if in some kind of seizure, shrieking out an inchoate Yiddish rage at her husband’s headstone: “Itchik, why did you do this to me?”

Barney’s oldest brother Ben, married and working as a bookkeeper, arranged to sell the store and used the money to send his mother to live in Colchester, Connecticut, where Itchik’s sister and elderly mother lived. Ben didn’t have enough room to take in his other brothers—and his young wife was already pregnant. It was yet another cruel twist in the fate of the Rasofsky clan: Isidore’s first grandson, named Yitzhak (Irwin) in his memory, was born a little more than a week after the murder.

Barney and Morrie were sent to live with their father’s cousin Henry Rasof, and the three youngest children were taken in by the Marks Nathan Jewish Orphan Home at Albany and 16th Street. Barney later remembered standing in front of the “gray, dingy-looking orphanage,” with fists clenched hard, vowing he would make enough money “to get them out of there.”

In his autobiography, No Man Stands Alone, published in 1957 (as dictated to coauthor journalist Martin Abramson), Ross says that the two men who killed his father got away with the crime—an elderly customer had witnessed the shooting but was too scared to testify. The killers’ escape, in Barney’s retelling, fueled his rage at the world, and in every street fight to follow, he could see the faces of the men who murdered his father. “The bitterness and hatred inside me made me a much tougher fighter,” he recalled. “Every opponent in a street fight seemed to remind me of Pa’s murderers and so I seemed to find extra strength in fighting them, or kicking them in the groin and making them scream in agony.”

With his mother drifting into madness on the farm in Connecticut, fourteen-year-old Barney lost his pain in the torrent of the Chicago streets. He wandered Roosevelt Road in the clawing cold—”a lost soul,” he later said. Technically billeted to his cousin Henry’s care, he was a ward of the wild West Side. He started to smoke and curse, and learned he could throw back bootlegged beer like a grown man. He had no time for his oldest brother Ben’s lectures, scoffed when Rabbi Stein asked why he hadn’t been to shul. He screamed that he no longer believed in God.

“In my terrible bitterness and hurt, I wanted to take my feelings out on something, and religion seemed the most logical thing to hit at. Religion had been the biggest thing in Pa’s life and what had it gotten him?… To teach Hebrew—to have anything to do with religious work—was now the last thing in the world I wanted to do.” He stopped wearing tzitzis under his shirt, rode the streetcar and handled money on the Sabbath, and began to eat ham and pig’s knuckles in restaurants.

“The only Jewish custom I continued to follow was to say the kaddish three times a day. But as far as I was concerned I wasn’t doing this for the sake of religion, but merely to pay my respect to Pa and to prevent his remains from turning to dust, which according to ancient belief was what would happen if he wasn’t mourned.”

Reader's Guide

From his humble origins on the hardscrabble streets of an immigrant neighborhood in Chicago, Barney Ross would become a petty thief, a champion boxer, a war hero, a gunrunner, and a man who conquered his morphine addiction. The following questions are ways to begin exploring Ross’ extraordinary, emblematic life. Jews and Boxing: A Lost History Barney Ross was among the best—and most proudly Jewish—American boxers, yet he is hardly remembered today. Why is Ross, a pioneer in promoting Judaism both in and out of the ring, forgotten, while Sandy Koufax, who refused to play on Yom Kippur, a hero? Why has pride of sports place been given to baseball players like Hank Greenberg and Sandy Koufax instead of boxers? Douglas Century tells us in Barney Ross that “Like so many Jewish prizefighters before him, Beryl Rasofsky used a nom de guerre to hide the truth from his overprotective mother.” What does this hiding tell us about Jewish views of violent sports? How has this cultural bias changed since Ross fought in the 1930s? Saul Bellow revolutionized the Jewish-American literary voice by evoking how intellectuals, boxers, and criminals rubbed shoulders in Depression-era Chicago. The intellectuals and criminals have been celebrated, but the story of the Jewish boxer remains largely untold. Why? “For a while during my adolescence I studiously followed prizefighting, could recite the names and weights of all the champions and contenders….From my father and his friends I heard about the prowess of Benny Leonard, Barney Ross, Max Baer and the colorfully named Slapsie Maxie Rosenbloom….In my scheme of things, Slapsie Maxie was a more remarkable Jewish phenomenon by far than Dr. Albert Einstein.” —Philip Roth, The Facts An American Jewish Hero Despite his gambling, drug use, and association with organized crime, Barney Ross is seen by many as a hero. How do we balance these “sins” with his “virtues”: devoting his early adulthood to getting his siblings out of an orphanage; wearing tzitzit under his clothes; publicly reciting the Psalms when fighting Japan during World War II; and publicly championing Zionist causes in an era when cel ebrities hardly did such things? Barney Ross’ public embrace of Jewish symbolism contrasts with a private life in which Jewish rituals and texts played little role. This is in contrast to some contemporary Jewish boxers like Dmitry “Kid Kosher” Salita, who are actually observant Jews. Is there anything to learn from Barney Ross about the conflict, or the disconnect, between public and private Jewish life? What do we expect from Jewish athletes or celebrities today? “Robert Cohn was once middleweight boxing champion of Princeton. Do not think that I am very much impressed by that as a boxing title, but it meant a lot to Cohn. He cared nothing for boxing, in fact he disliked it, but he learned it painfully and thoroughly to counteract the feeling of inferiority and shyness he had felt on being treated as a Jew at Princeton. There was a certain inner comfort in knowing he could knock down anybody who was snooty to him, although, being very shy and a thoroughly nice boy, he never fought except in the gym. He was Spider Kelly’s star pupil. Spider Kelly taught all his young gentlemen to box like featherweights, no matter whether they weighed one hundred and five or two hundred and five pounds. But it seemed to fit Cohn. He was really very fast. He was so good that Spider promptly overmatched him and got his nose permanently flattened. This increased Cohn’s distaste for boxing, but it gave him a certa in satisfaction of some strange sort, and it certainly improved his nose. In his last year at Princeton he read too much and took to wearing spectacles.” —Ernest Hemingway, The Sun Also Rises Supermen, Golems, and Boxers Barney in training Despite traditional strongmen like Samson and Judah Maccabee, the image of Jews usually precludes great physical strength. Why have Jews and non-Jews persisted in this belief? In the 1930s, while Jewish boxers like Barney Ross defended Jewish honor in the ring, young Jewish men like Jerry Siegel and Joe Schuster were creating the first superheroes. Historically, what role has the fantasy of unlimited power played in the Jewish imagination, from Samson to the Golem and beyond? And how has actual power played out in modern Jewish history? Despite being some of the best boxers of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Jewish fighters had to battle stereotypes of themselves as being canny and scientific rather than naturally strong or vital. In what way does this perpetuate the stereotype of Jews as being physically strange? And is there anything wrong in describing a “Jewish” style of boxing that focused more on wiles and surviving than brute strength? Ross’ physical feats in the ring and during wartime were followed by harrowing self-abuse. Is this a case of Jewish anxiety about power being vindicated, or merely one man’s struggle? In what way was Ross a kind of Golem who, once activated, was impossible to turn off? “As soon as the German army occupied Prague, talk began, in certain quarters, of sending the city’s famous Golem, Rabbi Loew’s miraculous automaton, into the safety of exile…There was, in the circle of its keepers, a certain amount of resistance to the idea of sending the Golem abroad, even for its own protection…. There were even a few in the circle who, when pressed, admitted that they did not want to send the Golem away because in their hearts they had not surrendered the childish hope that the great enemy of Jew-haters and blood libelers might one day, in a moment of dire need, be revived to fight again.” —Michael Chabon, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay Jews, Boxing, and Ethnic Relations In Barney Ross we see how the politics of the 1930s were made visible in the arena of boxing. For instance, the historic fight between Joe Louis and Max Schmeling was seen as a symbolic battle between America and Germany, as well a triumph for African-Americans. Jews and blacks were deeply connected in their support of Louis. What common enemy could inspire a black-Jewish alliance today? Many of Ross’ most famous fights—against Tony Canzoneri and the Jimmy “The Jew Beater” McLarnin—were spun into ethnic feuds by the media. The boxers hated their labels and rather admired each other. What does this tell us about how the media and other power brokers stoke ethnic tensions? Jews were such successful boxers in the 1930s that some non-Jews such as Max Baer (the villain in the Hollywood movie Cinderella Man) wore a Star of David on his trunks. Is this a dilution of Jewish identity, or a compliment?

More Videos

News and Reviews

Barney Ross reviewed as an important read

“If I were the education president every White House inhabitant claims to be, the reforms would begin with putting Douglas Century’s new biography, Barney Ross on the required-reading list.” Continue reading

Douglas Century does good by Barney Ross, says NYTBR

“This is an excellent story of a man and his times. And proof positive that time does not relinquish its hold over men or monuments. In a sport devoted to fashioning halos for its superstars, Ross wore a special nimbus, and this book properly fits him for that.” Continue reading

Barney Ross applauded

“It is not often that a modern biography ennobles not only its subject but the genre itself, but this is exactly what Mr. Century has accomplished, crafting a narrative as unsparing and inspiring as its subject.” Continue reading

About the Author

Douglas Century

DOUGLAS CENTURY is the author of Street Kingdom and, with Rick Cowan, of the New York Times best-seller Takedown. He is a frequent contributor to The New York Times, among many other publications. Born and raised in Canada, he lives … Continue reading